- Engine: 490cc air-cooled 4-stroke single, 79mm x 100mm bore and stroke, 7.12:1 (for English “pool” petrol) 9.3:1 (set up for American premium) compression ratio, 29.5hp @ 5,500rpm

- Top speed: 97mph (period test)

- Carburetion: Amal TT 36 type, 1-5/32in bore (stock) Amal Monobloc (on bike)

- Electrics: Lucas magdyno

75in (1,391mm)

Getting through the pandemic, with the accompanying isolation and worry, was difficult for many people.

Mike Rettie managed through fly fishing, gardening and finishing the restoration of this 1948 Norton International, a very fast bike for its era and an unusual find in the United States. Mike’s International is not only fast, but therapeutic. “It got me through Covid and transitioning to retirement,” he says.

Norton Internationals come from an era where the English Norton company was a top road racing contender and built technologically advanced machinery. In the 1940s, Norton riders were on the podium in most international events. While most 1940s motorcycles made do with a sidevalve or overhead valve engine, the Manx factory racers had dual overhead cams. The postwar production racers had telescopic forks and, from 1951, the Featherbed frame, which set new standards in fast handling. Although production racers had a single overhead cam, racers with a good resume might be allowed to buy a DOHC Manx from the factory.

Power to the people

If you wanted something that was street legal, but looked and performed like a Manx, you bought an International, basically a detuned Manx with lights. It came in both 500 and 350 versions, and was aimed at amateur riders who wanted to contest the Clubman’s TT race on the Isle of Man. One of the benefits of organized road racing in postwar Britain was access to gasoline.

Although the war was over, Britons were still dealing with the aftermath. England had huge war debts, and manufacturers were ordered to export as much as possible. Many items were rationed, but gas in particular was in short supply. Many motorcycle club members rode bicycles to meetings. The demand to export meant that many new motorcycle models were not available in the Home Countries. Frustrated English riders read about the wonderful new machines that were being shipped to South America, South Africa and especially to the United States, and gritted their teeth. A bright spot was the resumption of racing in 1946 with the Manx Grand Prix (an amateur event on production machinery) in 1946, and the iconic Isle of Man TT races in 1947.

Nortons in the U.S.

On the other side of the pond, imports of Nortons and other British two wheelers were ramping up fast. American GIs had become acquainted with lightweight, good handling British machinery during World War II. They liked what they saw, and English motorcycles became popular quickly. Gilbert Smith, the managing director of Norton, spent seven weeks traveling through the U.S. in September 1947, and wrote about his experiences in The Motor Cycle, a weekly British magazine. Although there had only been a small handful of prewar U.S. Britbike dealers, by 1947 there were 60 shops selling Triumphs, BSAs and Nortons in the U.S. Some 10,000 British motorcycles had been imported to the U.S. as of September of that year.

Unlike a British rider, who had to pull strings and hope to get a top of the line bike, an American rider just had to reach deep in the wallet. At the time, a Norton International cost $1,071.98. Although that sounds like a bargain, average U.S. family income at the time was $3,200 a year.

Imports of Nortons and several other makes were also promoted by the turmoil at Indian, then one of the two major American motorcycle companies. The new owner of Indian, Ralph Rogers, had bet the farm on a new line of lightweight singles that did not sell. As a condition of a $1.5 million loan from a British firm, Indian dealers were asked to carry several British makes, including Norton.

The Norton Internationals that were displayed in postwar American dealerships were a descendant of the factory race bikes of the late 1920s. After Velocette pioneered overhead cam engines on motorcycles, Norton followed with its own design a couple of years later. Norton factory racing success was followed by production racers for sale. First offered to the general public with a need for speed in 1932, these overhead cam singles had a 4-speed foot shift transmission. Valve spring steel in the 1930s was prone to break, and one cure tried was “hairpin” valve springs, horizontal springs whose ends bear on the rockers. Norton started using these in 1935. Hairpins are bulky and difficult to enclose, and, when better valve spring steel became available in the 1950s, they went swiftly out of fashion. Other prewar upgrades to the International were optional alloy heads and cylinders, and a plunger frame. In the late 1930s, Norton’s overhead cam race bikes were renamed Manx. The International name was reserved for the top of the line overhead cam street single.

After the war

England went to war in 1939, and civilian motorcycle production was suspended for the duration. When both the 350 and the 500cc Internationals reappeared in 1947, the cast iron engine was standard, although the alloy top end (from the Manx production racer) was available at an extra charge. The single overhead cam ran on a bevel drive shaft driven from the lower end. Ignition was provided by a Lucas magdyno, a combination magneto and generator which may have been the inspiration for several Lucas jokes. The carburetor was an Amal TT (a racing carburetor), but the muffler was the same as used on several other Norton models of the time. The gearbox had a low first gear to assist with kickstarting, with the top three gears closely spaced.

The Garden Gate plunger frame was one of the first sprung frames (the Vincent frame was another) that was proven to handle at speed. Front end suspension was upgraded from the prewar girders to Roadholder telescopic forks with rudimentary hydraulic damping. Both the gas tank and oil tank were large, and finished with chrome plating and black and red pinstriping. The stock muffler choked the engine, and one of the first things an owner would do would be to get rid of it and either race with a straight pipe or, if the bike was going to used on the road, bolt on an aftermarket replacement. In 1947, both major English motorcycle magazines had a chance to test a 500cc International with a Brooklands exhaust (a nonrestrictive but relatively quiet muffler). The Motor Cycle wrung 97mph out of the OHC single, despite the fact that the only gasoline available was so awful that the postwar International had only a 7.12:1 compression ratio in order to cope.

Tuned up and with a jockey aboard who knew how to ride this bike, the International won races. Geoff Duke won the Senior Clubman’s race on an International in 1949, Phil Carter won on another one the next year and Ivor Arber won on a third in 1951. In the United States, most races were off road or flat track, and the only real road race was held at Daytona. During the 1940s and early-1950s, Manx Nortons were regularly on the Daytona podium. Dick Klamfoth and Billy Matthews won Daytona on Manxes on such a regular basis that overhead cam machines were banned from American competition for the 1953 season. Bob McKeever raced an International at Daytona, and is the only person known to do so.

Some assembly required

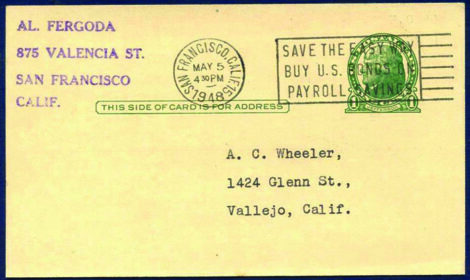

Most people who bought Internationals in the U.S. apparently just wanted to go fast on public roads. On the West Coast, San Francisco Norton dealer Al Fergoda sent postcards to his customers in 1948, advertising a 500cc (Model 30) International for sale with the Manx alloy barrel and head, Manx higher compression piston and Manx connecting rod. The Norton Owners Club in England has the factory records, and was able to confirm that the engine in Mike Rettie’s International was from one of the bikes shipped to Fergoda. The chassis is from a different 1948 International, making the machine a “mongrel.”

Mike has been working on this machine on and off for years. “A close friend began collecting bits for this bike in San Francisco in the early 1980s,” Rettie explains. “He made good progress to the point of assembling a roller in an ES2 chassis but ran out of enthusiasm at some point and gave the project to me.

“The first thing I noticed was that the rockers were not properly centered on the valves. As I dug into the engine, I found other problems which led me to tearing down the engine and eventually the whole bike. One thing led to another and I decided to try to find all proper Inter parts to assemble this machine. There must be major parts from at least half a dozen defunct Inters that found themselves reborn in this incarnation.”

Mike was then working as a machinist in a shop that specializes in high end sports automobiles, and knows how to assemble an engine. “The cylinder head is bimetallic — bronze and aluminum. It was tricky to repair — I had to have the valve seats in the bronze “skull” braised up to revive them and then re-cut the seats.”

When he started looking for parts, overhead cam Norton enthusiasts came out of the woodwork to help. The frame was found in rural Oregon, the gas tank was bought from an eBay merchant on the East Coast, and a friend parted with an oil tank in his stash. Different members of the Norton Owners Club donated parts, including the larger front hub and brake. “I collected parts from all over. Paul Norman and Ian Bennett in the U.K. and Ken MacIntosh from New Zealand were standouts,” Mike says. “A friend in Germany came up with the alloy head and barrel. The engine was supplied with a Manx connecting rod, the same as when originally built. A new oversize Manx piston was also located in Germany.”

A lot of parts are unique to the International, including the rear brake pedal, and are scarce on the ground. When Mike couldn’t find something, he made it, including the valves and valve guides. The special tools needed in International assembly have disappeared in the mists of time, so Mike made them as well. With all machining completed and all parts in house and Mike newly retired from his long-term job, work on the International sped up. “It was tricky to put this bike together. There is a lot of careful shimming to do and in the proper order to get the cam drive backlash correct. The cam box is not part of the head, and there were a lot of old, worn parts. The timing cam lobes are infinitely timeable. The oil pump is an interference fit in the crankcase.”

Besides general engine and machining knowledge absorbed from years working with engines, Mike had a special guide, Garden Gate Manx, The Book About My Bike, C11M14566 by Niels Schoen, a Dutch CAD engineer. Schoen inherited a 1947 Manx from his Uncle Ko, somehow managed to get it into his fourth story walk-up in Rotterdam, Holland, took it apart, reassembled it, and documented the process on the SolidWorks program. The book (self-published and available from the author) contains a digital rendering of all the assemblies on the motorcycle, with factory part numbers and helpful advice.

Back together

Eventually, the International was back in one piece, with the engine as it would have been shipped to San Francisco, including a 9.3:1 compression ratio to suit the gasoline available in the U.S. It also has some internal improvements and a few external ones. Ian Bennett supplied roller rockers, which are quieter, reduce cam wear and require much less oil. Commando fork internals are a vast improvement on the 1948 version of Roadholder telescopics, which had a minimum of fork damping. Stainless steel spokes don’t rust. An AMC clutch fits nicely in the cases and doesn’t drag.

Mike also substituted a Monobloc Amal carburetor for the stock Amal TT mixer in order to simplify the initial start-up and break-in. Monoblocs are meant for the road, have an air cleaner, and have provision for a good idle. The tail light is also not standard. The stock unit is the size of a fifty cent piece and probably not safe for today’s traffic. The one on the bike is there because Mike liked the Buck Rogers look. The 8-inch front brake is from a later version of the International, replacing the stock 7-incher.

“It started in December 2020 on the fourth kick. It has a manual advance, and once I backed off the advance a little it started right up.” Unfortunately, what also started up was oil leaks. “It’s difficult to make an International oil tight. The rockers are not entirely enclosed.” Mike worked on the leaks and started taking the bike on longer rides. He now thinks the leaks are fixed — for now. One item that is not fixed is the wet sump problem. Internationals tend to “wet sump,” meaning oil drains from the tank to the bottom of the engine as the bike sits, often leaking onto the floor and making the bike hard to start. It is possible to put a turnoff valve in the oil feed line, but many owners of bikes with turnoff valves forget to turn the oil feed back on, with disastrous results.

Although big singles are often difficult to get running, Mike says that this International is a “piece of cake to start, with a quick carb tickle, the proper spark advance, and the judicious use of the compression release.” Once underway, “It shifts slowly and deliberately, but revs freely and briskly accelerates. The new clutch does not drag. It’s so old, I am surprised how quick it is. The handling is not bad over 50mph, but the rear springs are stiff, and the ride is pretty harsh for my old bones. It takes getting used to. The bike also stops reasonably well, but riding through traffic is no fun. In order to really enjoy this bike, you have to adjust your expectations and get out to the countryside.”

“The best thing about the whole project was all the people I met trying to run down parts and services. When I was working, I worked on Ferraris, Maseratis, Alfas and some pretty obscure machinery. I used all the things I learned and tried to do as much myself as possible. Without the help of my friends and workmates, the old beast would still be a heap of parts hiding out in the depths of my basement.” MC