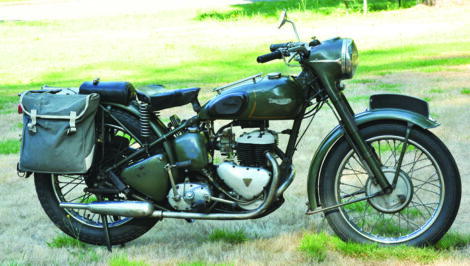

Follow the British Triumph military motorcycle trail starting with the Model H through wartime to the 1948-1964 Triumph TRW 500.

- Engine: 499cc air-cooled, side-valve parallel twin, 63mm x 80mm bore and stroke, 6:1 compression ratio, 18hp @ 5,000rpm

- Top speed: 70mph

The cavalry had long been a dominant force in the fighting field by the time of World War I. But things were about to change, and rapidly. The mounted soldier was going to get a new mount.

Anyone who has seen the movie or theater productions of War Horse can’t fail to have been moved by the wholesale slaughter of cavalry horses on the battlefields of France and Belgium — not that their riders fared any better. With the arrival of more accurate artillery, armored cars, machine guns and tanks, cavalry was suddenly obsolete.

But there were other roles undertaken by mounted soldiers that a new invention — the motorcycle — could perform better, faster and more safely. Not in the traditional cavalry charge, obviously, because of the need to control the machine with both hands! Adding a sidecar with a gunner on board partially offset this limitation, but armored cars performed better in that role.

Where the military motorcycle principally scored was in communications. It was (relatively) stealthy, speedy and nimble, allowing it to deliver dispatches quickly while also being a trickier, lower-profile target for snipers.

Arguably, first to recognize these benefits was the British Army, which introduced the Triumph Model H, also known as the “Trusty Triumph” in 1915. (Ironically, the Triumph company was founded in 1902 by German immigrant Siegfried Bettman, and used a Bosch magneto!)

Not that Triumph had it all their own way. After they had won the Isle of Man TT in 1912 and earned team prizes in the International Six-days Trial, Douglas Motorcycles were also asked to build machines for the British army and provided at least 25,000 350cc “fore and aft” side-valve, 2-speed flat twins. (It’s said that an appropriated “Duggie” inspired BMW to produce a flat twin themselves in 1921 — albeit with the cylinders in a different orientation.)

The model H used Triumph’s own 550cc single cylinder side-valve engine with one camshaft operating both valves, and a Triumph carburetor. The drive went to a 3-speed Sturmey-Archer countershaft gearbox with drive to the rear wheel by leather belt. Claiming all of four horsepower, the Trusty proved rugged and reliable in the field and remained in production until 1923. At least 30,000 were employed during in World War 1.

3TW

With war looming again in Europe in the late 1930s, the Ministry of Supply looked to the vast British motorcycle industry to supply machines to meet their specification of 250cc or greater with a weight of less than 250 pounds — a target that neither the 500cc BSA M20 nor Norton 16H could match.

Canny as ever, Triumph’s Edward Turner proposed a bike based on the company’s existing 350cc Tiger 85 twin. Designated Model 3TW, it used an all-alloy 350cc OHV parallel twin in unit with a 3-speed gearbox, and the gas tank serving as a frame member. And while it handily exceeded the MoS requirements on paper, the 3TW’s powerband proved too peaky for off-road use, with most power coming in above 3,000rpm. Triumph made a heavier flywheel for the 3TW and fitted a smaller carburetor to address this issue. The production 3TW was to use an iron head and cylinders because of aluminum shortages — yet still weighed under 270 pounds. Turner’s then assistant at Triumph and later business adversary Bert Hopwood was unimpressed with the 3TW, noting that it was under-engineered and “would have proved troublesome” and “not suitable for the rigours of warfare.”

But the 3TW would never go into production. On the night of November 14, 1940, the Luftwaffe blitzed the city of Coventry, destroying both the Triumph factory and the first batch of 50 3TWs as well as the drawings, specifications and tooling. Wrote Bert Hopwood about the 3TW in his book Whatever Happened to the British Motorcycle Industry, “I still feel that … Hitler did our War Office a favour.”

5TW

Triumph moved to temporary premises in Warwick while a new factory was under construction in the village of Meriden, between Birmingham and Coventry. The company continued supplying motorcycles to the military, but these were the single-cylinder 350cc models 3HW and 3SW based on the pre-war OHV 3H and side-valve 3S.

It was Hopwood who designed the next Triumph military bike. Turner had left for BSA over a dispute with Triumph owner Jack Sangster. Hopwood has sometimes been accused of bias against Turner’s designs based on “not invented here,” and it’s true he and Turner had their share of clashes on engineering theory and practice. But Hopwood’s criticism was often justified. He was scathing of the 3TW’s shortcomings, many of which could have resulted from attempting to meet unrealistic MoS specifications. Hopwood’s response was a completely new 500cc side-valve twin, the 5TW — though it still owed much to Turner’s 1937 Speed Twin.

Hopwood adopted the Speed Twin’s cylinder dimensions of 63mm bore and 80mm stroke. But instead of a pair of camshafts operating the valves via external pushrod tubes, Hopwood’s design used a single camshaft at the front of the engine operating all four valves via tappets. These were adjustable in the timing chest, accessed by removable covers on the front of the cylinders. A single casting in iron formed the cylinders with iron cylinder heads, aluminum still being in short supply. Ignition and lighting were courtesy of a “Dynomatic” dynamo/coil system using a chain-driven DC generator behind the cylinders with integral contact breaker and automatic ignition advance/retard.

In spite of all the design work and testing, the 5TW turned out to be essentially a “vanity” project. Knowing that Turner was then developing a similar military machine at BSA, Sangster was determined to have the 5TW revealed before BSA’s bike. Which it was.

TRW

And while the 5TW never went into production, it formed the basis for the 500cc TRW. Turner had returned to Triumph in 1943 and applied his own ideas to the new bike. It was first shown in 1946 and was built to a particularly detailed MoS specification. This required a top speed of better than 70mph and consumption of better than 80mpg at 30mph. Weight was to be less than 300 pounds; braking to a stop from 30mph in less than 35 feet; loaded ground clearance of minimum 6 inches; ability to ford 15 inches of water; and climb a 45 percent grade, with a stop and start on the same slope. The TRW proved a reliable and durable mount over at least two decades, employed by forces all around the world. It stayed in production from 1948 until 1964 with around 16,000 built.

Though superficially similar to the 5TW, the TRW incorporated a number of detail changes: a BT-H magneto replaced the Dynomatic ignition with an engine-speed AC alternator — a first for British motorcycles — inside the primary. Chain drive to the camshaft was nixed in favor of spur gears with a large idler, and the transmission gained a fourth gear. Carburetion was by Amal type 6 on the prototype, before being replaced with an SU and eventually a Solex in production.

With the carburetor mounted at the rear of the block, the intake charge passed between the cylinders to the valves at the front, aiding engine cooling, but also picking up unwanted heat to the intake gases in the process. A telescopic front fork had been introduced on the 5TW and continued on the TRW. No suspension was used at the rear, the subframe being bolted up to the main frame.

“They also serve who only stand and wait”

Sadly, for Triumph, the British military had an embarrassment of surplus motorcycle inventories by the end of World War II. Many were repurposed for the civilian market by the simple expedient of painting over the olive drab with gloss black. But it also meant that the biggest potential market for the TRW almost ceased to exist. However, though it was unfortunate for the participants, there was still plenty of unrest in the world; like the Malayan Emergency, the civil war in Greece and the Suez crisis, and the TRW was widely used.

Eventually, most TRW production found its way to British Commonwealth countries, principally Australia, Canada, New Zealand and (then) Pakistan; though the British Royal Air Force also bought a quantity. Many ended up in long-term storage, and were steadily released for civilian purchase over the years, occasionally showing up at auction still in their shipping crates.

From 1948-1953, the TRW used a BT-H magneto for ignition, switching to coil ignition with distributor. A second coil was added for the final production run to 1964.

Specially modified TRWs were the motorcycle of choice for the White Helmets motorcycle display team of the Royal Corps of Signals until around 1969, when they were replaced by 500cc Tiger 100s and later 750cc TR7V Tigers.

Tom Mellor’s TRW

Vancouver’s Tom Mellor is the holder of four AMA speed records at Bonneville Salt Flats, with his fastest time in the 1000cc APS-PF class (altered, partially streamlined, pushrod, fuel) of over 207mph riding a very special 1969 Triumph Trident streamliner he built himself. Bikes that Tom has built or tuned (mostly Triumphs) hold records in 17 classes!

And while he runs a nicely period Triumph T160 set up for touring, he also has an affection for the TRW he has owned for 55 years. Around 1968, a friend was looking to get into motorcycling and bought a TRW from Vancouver military surplus store Three Vets. After just a week he decided the TRW wasn’t for him and Tom bought it from him for $99. “I’ve just used it ever since,” Tom says.

In that time, he’s added 40,000 miles, mostly around the city; but for many years it was his daily driver, taking him to his job with CP Air at Vancouver airport. The TRW came in for a fair amount of abuse. One of the problems: it was just a five-minute ride to work, so the TRW had no chance to properly warm up “I’d go peeling across the (bridge to the airport), flat out at 70mph,” Tom says.

The TRW accepted this abuse until one day a tappet end let go with a bang, necessitating new cylinders and cam followers. These were readily available by mail order from Nicholson Brothers in Calgary. Other than that, the engine has never been apart.

“That was 20, 30 years ago. They had brand new cylinders, heads, rods, everything quite cheap.”

The TRW has happily accepted its role as a commuter and shopping bike, and almost never overheats, even when idling at a stop.

“It’s great for just doing some shopping, because if you get stuck in traffic, it doesn’t care.”

It also helps that first gear is very low, allowing the TRW to drive on rough terrain at walking pace, no doubt a nod to its role as a parade escort. “Normally, you don’t start off in first gear,” Tom says, “because it’s so low. You start off in second. And it’s very reliable. I mean, the worst thing was — if you leave it out in the rain, the water can get into the distributor. And then the points get wet, then you have a hard time starting it.”

Tom fixed this problem by sealing the distributor with silicone. Adjusting the valves is also a snap. A special tool was included in the TRW’s tool kit, but Tom prefers a simpler approach. “All you do is take the cover off the front and there’s a ratchet. You just take a screwdriver and go click, click. And that’s it. There’s no undoing nuts or anything.” The valves rarely need adjustment anyway, says Tom. The only time any serious adjustment was needed was when the bike fell on its side and the throttle jammed open. “Then you’ve got to adjust them again,” says Tom. “Other than that, they never need adjustment.”

So does the TRW make a good entry-level bike? “They’re pretty slow. I mean, they say it makes 19 horsepower. I’m considering keeping it because it’s now an exit-level bike!” Tom jokes. His touring T160 weighs 540 pounds — around 200 pounds more than the TRW — and getting it on the centerstand can be a challenge. “Because when I can’t handle these things, and they’re getting too heavy, the TRW is so light, and the center of gravity is so low. It’s so easy to ride. The clutch is extremely light.”

The TRW is easy on consumables, too. Tom is fairly sure it’s still wearing its original final drive chain and still has the distinctive, pink-colored Lodge spark plugs fitted at the factory. The engine has never been apart (except for the dropped tappet incident), and the only other item to give trouble was a slipping clutch. Tom fixed this by surface grinding the clutch plates flat. “Because they’re just stamped out and they’re not perfectly flat,” says Tom. “Now, it doesn’t slip at all.”

The day before our photo shoot, Tom put in fresh gas and test started the TRW, which had been sitting in the basement for four years. “You can start it without the battery,” says Tom.” I forgot to hook up the battery, and it started right up.”

Of course, on the day of the shoot the TRW refused to start at all. Tom tracked the problem to a stuck needle valve in the carburetor. Some carb cleaner and application of an air line, and the TRW was soon running again. The needle and seat are not otherwise serviceable because they’re pressed together in one unit. But they’re common to older Volkswagens, which also use a Solex carb with the same needle/seat. Final thoughts on the TRW?

“Well it’s docile,” says Tom. “It’s not fast. Passengers don’t like to ride on it. My grandson wouldn’t ride on it. It’s so bumpy because there’s no springs. No springs in the seat either. It wasn’t really designed for passengers, I’m sure.”

But that’s really his only criticism. So with its future role as an “exit-level” motorcycle assured, Tom’s TRW is likely to stay in the fleet for some time! MC

Alphabet Soup

There’s much confusion in printed accounts of Triumph’s World War II-era products, with photographs of the company’s military machines sometimes mislabeled. Not surprising, perhaps, as the company developed five different machines around this time. Essentially, the designations worked like this: W for military; 3 for 350cc; 5 for 500cc; T for twin; H for overhead valve; S for side valve. That said, the 3TW used overhead valves, and the 5TW side valves … And the “R” in TRW? The letter R was later used to identify the off-road Trophy range in Triumph’s catalogue.

Here is a list of Triumph’s World War II-era military machines:

- 3SW 343cc SV single based on the pre-war 3S, non-unit, 4-speed, 70mm x 89mm, girder fork.

- 3HW 343cc OHV single based on the pre-war 3H, non-unit, 4-speed, 70mm x 89mm, girder fork.

- 3TW 349cc OHV twin (Edward Turner) based on the pre-war Tiger 85. Unit construction, 55mm x 73.4mm, 3-speed, girder fork. 50 built.

- 5TW 499cc SV twin (Bert Hopwood) non-unit, 4-speed, 63mm x 80mm, chain-driven cam, “dynomatic” lighting/coil ignition with auto advance, telescopic fork. Prototype only.

- TRW 499cc SV twin based on the 5TW, non-unit 3-speed (later 4-speed), 63mm x 80mm, gear-driven cam, alternator/magneto (to 1953) replaced by coil/distributor.