By 1950 motorcycle enthusiasts were beginning to wonder if the Harley-Davidson Motor Company was ever going to fully engage the 20th Century. After all, Harley still offered a model powered by an aging flathead engine that was linked to a 3-speed transmission — with a hand shifter.

By then many progressive companies offered models powered by overhead-valve engines coupled to foot-shift 4-speed transmissions. For the time that was front-line technology.

Then in 1952, as if slowly yawning while emerging from a peaceful winter slumber, Harley-Davidson revealed its new K Model, featuring — drum roll, please — foot-shift and a unit construction engine in which the transmission shared the same confines as the engine’s lower end. Even though the K Model still featured side-valve combustion chambers (aka, flathead), the new K Model 743cc (45 cubic-inch) engine was a breakthrough design for the American brand. The following year future NASCAR driver Paul Goldsmith won the Daytona 200 — still run on the fabled Beach Course — aboard a KRTT model, Harley’s race-ready version of the K Model.

Beachfront property

A dynasty, of sorts, was in the making as KRTT riders won seven more Daytona 200s on the original beach course before racers migrated to the new and modern Daytona International Speedway in 1961, with race action restricted to the track’s infield portion only. AMA officials insisted on bypassing the daunting 31-degree, 20-feet high, banking for fear the parabolically shaped asphalt would promote speeds too dangerous for the motorcycles’ tires and brakes. (Welcome, again, to the 20th Century.)

Even so, the hard pavement suited the KRTT’s bullish power as Roger Reiman gave Harley its first Daytona 200 win on the new paved circuit. The next year Don Burnett scored Triumph’s first Daytona 200 win ever, and then Ralph White on a KRTT won the final “infield” Daytona 200 in 1963. Reiman and his KRTT then christened the high-speed banking that’s used to this day, posting consecutive wins in 1964-1965 before Triumph led another British Invasion that gave American riders Buddy Elmore and Gary Nixon their wins in 1966-1967 respectively.

By that time the KRTT began showing its age, the 1966 variant producing an estimated 48 horsepower at 6,500rpm. “Torque is the flathead’s forte,” wrote Cycle magazine’s editor, Gordon Jennings in the July 1966 issue, “and the brutish 50 ft/lbs at 5,000rpm provides the searing acceleration that wins races.” Even so, Harley’s race team manager Dick O’Brien confessed that the legion of KRTTs fielded by The Motor Company for 1967 had been outgunned by the British bikes.

It was time for a rethink, and OB and his posse withdrew to Milwaukee, where they gave deep thought about ways to improve the KRTT for 1968’s Daytona 200. O’Brien hated to lose, so immediately following the 1967 season (and with Triumph’s Gary Nixon the new reigning AMA Grand National Champion, a fact that gave OB fits at night), he confirmed that a squad of seven riders would wear the orange, black and white colors for 1968’s 200. The list included Bart Markel (1965 and 1966 GNC), Freddy Nix, Mert Lawwill, Dan Haaby, Walt Fulton Jr., Roger Reiman and Calvin Rayborn.

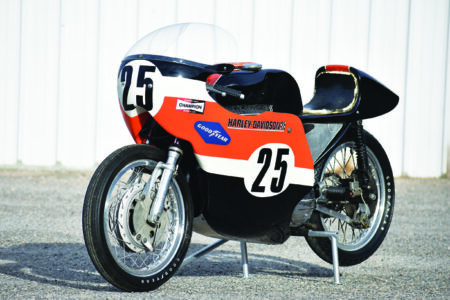

The 1968 bikes were based on the new Lowboy frame (with a lower steering head and frame backbone) that Harley had pressed into service mid-season in 1967. The frame, crafted by Ralph Berndt, offered less frontal area and a lower center of gravity, creating a more responsive chassis in terms of handling and steering through corners. The chassis included a lightweight H&H rear disc brake coupled with the proven Ceriani 4-shoe 230mm-diameter front brake mounted to a shorter Ceriani telescopic fork. Rear suspension included a pair of Girling rear shocks.

Next, attention shifted to aerodynamics, using a more efficient wind fairing that the Wixom Brothers (Dean and Stan) in Long Beach, California, developed. With assistance from engineers at nearby Cal Tech, Stan and Dean created a more compact and slippery shape that fostered more top-end speed on Daytona’s banking. An equally aerodynamic seat was part of the package, and for rider comfort the seat’s cushion was made of Ensolite, a soft, resilient vibration-absorbing plastic. The Wixom Brothers also designed a fuel tank formed so that riders could tuck their knees and elbows out of the wind stream. A baffle system inside the tank helped contain fuel slosh during hard braking and cornering.

Various fairing designs were tried, with each test session manned by the team’s fearless manikin nicknamed Sierra Sam, whose job was to serve as the surrogate rider in the wind tunnel itself. After strapping Sam onto the bike a huge propeller, powered by a Word War I submarine diesel engine, generated wind forces up to 160 miles per hour through the 10-foot-diameter wind tunnel so that engineers could gauge and check the fairing’s aerodynamics. Eventually one fairing proved superior to the others.

Throughout, OB and his crew addressed the aging flathead engine itself. Bob Garver, a Harley dealer in Kansas City, developed a new two-carburetor manifold for the 16-year-old engine’s intake that carried a pair of diaphragm-controlled Tillotson carburetors. As a bonus, the compact carburetors didn’t protrude as much as the single Linkert they replaced, allowing for an even more aerodynamic package.

C.R. Axtell, with prodding from dirt track specialist Neil Keen, discovered additional power lurking within the flathead engine’s convoluted intake system. Domed, rather than flat-top pistons supplied by Jahns were matched with some very creative reconfiguring of the combustion chamber’s fuel/air flow pattern and revised ports. The combination, matched with Harley’s J and K cams, noticeably improved acceleration and top end. As OB told Cycle World‘s editors just before Daytona Speed Week, the new twin-carb engine clearly outperformed the 1967 single-carb engine, which cranked out 52 horsepower at 7,000rpm to the rear wheel; the 1968 engine also peaked at 7,000rpm but, as OB pointed out, with noticeably more horsepower. How much more he wouldn’t reveal, but most rail birds figured that 55, perhaps even more, was certainly the minimum figure.

As usual, the Harleys would roll on Goodyear race tires, and with that matter settled, it was off to Willow Springs Raceway, a nine-turn, high-speed, racetrack nestled deep in California’s Mojave Desert, for testing. After numerous fast laps by Rayborn (who, conveniently, resided in nearby San Diego, California), the Daytona-bound KRTT was deemed ready, later confirmed by Reiman’s top-qualifying speed of 149.080mph for the 200.

Raceday dawned …

Clearly, much of the off-season work paid off for Harley’s KRTT. “The H-Ds were handling very well,” wrote Ivan Wager in his Cycle World race report, adding, “H-D’s new combustion chamber design permitted a more tractable power band.” The combination especially suited Rayborn, who applied it early in the race, but only after his — in Wager’s words — “semi-crash” during the fifth lap in Turn 1 where the Harley’s rear tire lost traction, prompting Rayborn to literally drag his knee for ballast until uprighting the bike so he could carry on as if nothing happened.

But one thing in particular actually did happen: On his way to victory Rayborn lapped the entire field. Actually two things happened — Rayborn also became the first Daytona winner to average over 100mph. 101.29mph, to be precise.

Harley-Davidson had set out to win the 1968 Daytona 200, and their success was a textbook example for every schoolboy to follow — do your homework and you’ll succeed.

Shortly after Rayborn’s domination at Daytona Speedway Ivan Wager was invited to sample the winning KRTT for Cycle World at Riverside International Raceway in Southern California. Wager’s first observation included a close examination of the Harley’s Goodyear tires that had been scuffed mercilessly along their edges, leading the desk jockey to write that there was noticeable scuffing “on the sidewalls for at least an eighth-inch farther [up] than the last rib. From these indications, it is obvious that Calvin was earning time from good riding, rather than brutal treatment of his machine.”

Wager also noted that the flathead engine pulled strongly from 4,500-7,000rpm, further stating “acceleration is strong (boy is it strong): however, there is sufficient flywheel effect to give the rider the feeling that everything wants to go from the rear tire to the road.”

Based on the bike’s speeds at Daytona, coupled with his seat-of-the-pants experience at Riverside, Wager figured the KRTT engine produced about 56 horsepower. Moreover, “braking is excellent,” and handling was “truly first rate.”

Daytona 200, 1969 — Harley’s last first

Of the original seven Harley team bikes entered in the 1968 Daytona 200, only one finished. But that one bike — Rayborn’s KRTT — finished where it counted most; first place. The other team bikes had either broken or crashed out, leaving Rayborn to share (and enjoy the place of honor — center stage) Victory Circle with Yvon du Hamel and Art Baumann, both on (gasp!) Yamaha 350 2-strokes.

Change was in the wind, and eventually would see 750cc 4-strokes with overhead valves and cams, not to mention a gaggle of new 2-strokes that were unquestionably faster yet unreliable, as evidenced by their shredded rear tires (speed) and frequent engine seizures (reliability). Plus an AMA rule change for 1969 finally allowed 5-speed transmissions; in 1968 the 2-strokes, originally equipped with 5-speed trans, were essentially handicapped because rules allowed only 4-speed trans, forcing the Yamaha and Suzukis teams to remove one gear from their bikes. That changed in their favor for 1969.

All that aside, Harley-Davidson checked in for the 1969 race with their tried and trusty KRTT, now sporting megaphone exhausts, a first for Harley (but still with 4-speeds). The team also boasted Cal Rayborn who, many race experts felt, was probably the best road racer in America, if not the world. And race fans the world over were about to find out if that was boastful bravado or fact because the 1969 Daytona field included several of Europe’s top Grand Prix stars.

Yet before Speed Week played out prior to qualifying, the herd of KRTTs proved to be slower than in 1968. More troubling to O’Brien and company was the KRTT’s reliability, which was mysteriously questionable at best during Speed Week. A lot of head scratching occurred in the Harley garage as qualifying approached. In the end top-qualifier was Yvon du Hamel and his Yamaha 350 2-stroke at a sizzling 150.01mph; Rayborn was eighth-fastest, but top Harley qualifier, with a speed of 144.76mph.

Rain, rain, go away!

Within a few laps of racing Mother Nature began pelting riders and racetrack alike with raindrops that eventually turned into a deluge. AMA officials decided the intimidating puddles dotting the track’s surface posed too much of a danger, so racing was ceremoniously postponed until the following Sunday.

When the track reopened a week later, the Harleys appeared more responsive, and as the race itself proved, more reliable. During the time-out Harley mechanics had rebuilt their engines to thoroughly blueprint their KRTTs’ internal parts. Their extra attention to detail proved beneficial, and team bikes were back where OB and the boys felt they should be — up front and in contention.

Eventually, Rayborn won again, doing so in his classic style through hard riding, prompting one magazine to suggest in its race report that he “outlasted a few, outran the rest, and won the 200-miler for … the second time.” In addition, Lawwill’s fourth-place finish on his KRTT sandwiched a pair of 2-strokes ridden by Ron Grant (second, Suzuki 500) and Mike Duff (third, Yamaha 350), followed by Harley riders Markel in sixth and Haaby in 10th.

Despite those good fortunes, the KRTT was pretty much at the end of its run. In all, Rayborn’s Harley won at Daytona, Loudon and Indianapolis in 1968 and Daytona, Heidelberg and Indianapolis in 1969. Yet the KRTT was soon to be replaced by Harley’s XR750 that featured overhead valves, among other improvements. Rayborn’s first-place at Laguna Seca in 1972 aboard the XR750 proved to be his and Harley-Davidson’s final AMA road race National win ever. He would lose his life while racing in an obscure New Zealand road race, riding a Suzuki 500 2-stroke, in early 1974.

And what became of Rayborn’s double Daytona winner? As obsolete race bikes go, it was relegated to the back of the race shop, then temporarily loaned to Reiman for some further race action before Harley-Davidson dealer Buddy Stubbs acquired it, with intentions to enter the 1970 Daytona 200. However, his plans got nixed when, at about the same time, his budding dealership gained traction, forcing him to spend more time at the shop rather than the racetrack.

A short time later Stubbs’ friend, the late Stephen Wright (perhaps best known for his authoritative books on American Grand National racing) offered to buy the bike. As the bike’s current owner, Mike Iannuccilli, picks up the story, “Stubbs refused to sell it, but Steve told him that everything has a price.” Steve talked some more, Stubbs listened some more, and eventually “the price” popped up in their conversation, and shortly thereafter Wright received his new collector’s bike, Cal Rayborn’s double-Daytona winner. However, by then few people realized, or perhaps appreciated, that this was Rayborn’s double-Daytona winner.

Eventually, though, the historic KRTT was passed along to Mark Mahler (as Wright had said, “everything has a price”) who later sold it to a collector in Japan. By then nobody in the vintage racing community knew the exact whereabouts of Rayborn’s famous KRTT. That included Mike Iannuccilli who had become enamored by KRTT racers in general. But he wouldn’t settle for just any KRTT. Mike wanted Rayborn’s double Daytona winner. And so Mike began his quest to locate the bike that, as he was to find out later, has an interesting “birthmark” that clearly identifies it as Rayborn’s Harley.

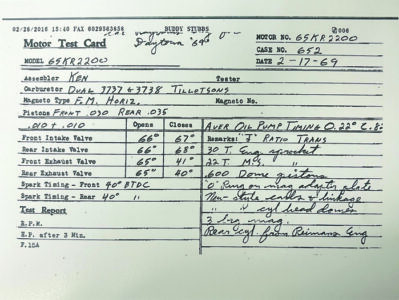

The birthmark is found in the engine’s number stamping on the left case. According to copious hand-written notes that the Harley race team maintained, the engine wore number “65 KR 2200” that a team mechanic hand-stamped when the flattie engine was enlisted for race duty. Now here’s the catch; the stamping is considered a “birthmark” by those familiar with it because the letter “K” is not really a K at all. For whatever reason, whoever stamped it probably didn’t have access to a bona fide “K” punch, so he improvised, selecting a “1” punch from the tool box, stamping it into the alloy case to form the vertical left side of the letter; he then juxtaposed the “V” punch, positioning the V sideways in relation to the “1” to form a rudimentary “K” on the engine case. At a glance, or to the unknowledgeable eye, the bogus K looks natural within the entire engine serial number sequence — 65 KR 2200. Hold that thought as we join Mike who begins his search for Rayborn’s ever elusive KRTT.

The search continues

Mike told his friend and historian in Texas, Bill Milburn, about his search for Rayborn’s Harley, and now there were two pair of eyes on the lookout. The path led to a KRTT road racer in Japan that Bill spotted on a vintage bike website. After further investigation, plus numerous e-mail exchanges with a certain KRTT owner in Japan, they accessed the KRTT’s engine number, only to confirm that it wasn’t Rayborn’s Harley.

Mike exhibits the tenacity of a pit bull when he hunts down his bikes, so eventually he gained the name of another KRTT owner in Japan. Turned out, too, that the owner was interested in selling. Mike eventually obtained a photo of the engine number, plus the assigned numbers found on the bottom sides of each case half. They all matched what Bill knew about the Rayborn Harley, so Mike had the owner send him clear photos of them and the “birthmark” number with its bogus “K”. And after careful scrutiny by Bill, Mike received a phone call from his friend in Texas. “That is it,” Bill told Mike, and after the usual bargaining, the Rayborn Harley was sent back to America where it joined Mike’s growing collection of former championship and champions’ race bikes.

Mike contacted Jim Belland to freshen up the engine to its 1969 form. Jim was formerly the H-D race mechanic for Mert Lawwill and Mark Brelsford in the Rayborn Harley era. The original 1968 engine was built by Jerry Foshey and Ken Rehfelt in Harley’s race shop, and the following year Rehfelt built the 1969-winning engine. “All hardware and parts are identical to [what was used in] ’69,” Mike states.

Clearly, the Rayborn Harley is a fine example of Daytona’s most famous winners. It, along with many other race bikes that Mike has in his collection, is displayed on a rotating basis at Red Rock Harley-Davidson on the outskirts of Las Vegas, Nevada.

Beyond this KRTT’s historical significance, the Rayborn Harley is special to this author because years ago during a phone interview with Dick O’Brien, our topic of discussion drifted to the late Cal Rayborn who, I knew, OB treated like his own son. At one point I inquired if he had any particular Rayborn memorabilia that was especially meaningful to him. OB said that he did — a tribute Rayborn racer that members of Harley’s race team had assembled for OB’s retirement in 1983. OB’s voice drew soft when he added, “And I’m never going to give that away.”

Maybe Stephen Wright was wrong — everything doesn’t necessarily have a price. If the late Richard H. O’Brien were here today, he’d probably tell us just that about his own Rayborn Harley. In the meantime, and much thanks to Mike Iannuccilli (with Milburn’s help), we all can enjoy what has become known as Rayborn’s Harley — Daytona’s 1968 and 1969 winner. MC