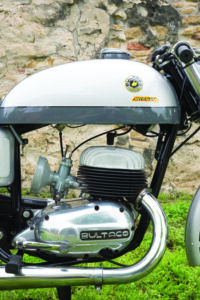

1965 Bultaco Metralla

Claimed power: 20hp @ 7,000rpm

Engine: 196cc air-cooled 2-stroke single, 64.5mm x 60mm bore and stroke, 10:1 compression ratio

Weight: 218lb (99kg)

Fuel capacity: 3.7gal (14ltr)

The tasty Texas Bultaco featured here isn’t served with salsa and chips — it comes with one cylinder, two wheels and a boatload of grins.

The United States was Bultaco’s largest market in the 1960s, but beyond the offroad world of trials and motocross, the Spanish company was not well-known and never attained more than cult status here. That’s a pity, because as the lovely Metralla on these pages proves, Bultaco also made exceptional street bikes.

Bultaco’s beginnings

Francisco Xavier Bultó, popularly known as Paco Bultó, cofounded the Montesa motorcycle company in 1944 and helped develop the company’s 125cc race bikes that were so successful in the 1950s. The Spanish economy hit a slump in 1958, adding to the financial strain Montesa was already experiencing following its recent move to new, larger premises.

The company chose to cut costs by withdrawing from racing, also eliminating its competitions department, as Moto Guzzi, Gilera and Mondial had already done. As a board member, Bultó strongly disagreed with this decision — he believed racing “improved the breed” and boosted sales. The company would not be swayed, so Bultó resigned and made plans to pursue his other business interests, which included textiles and a company making pistons and piston rings.

Shortly thereafter, a group of Bultó’s former colleagues invited him to dinner. At the meal, the 16 Montesa employees gathered together echoed Bultó’s strong feelings about the racing program. They were poised to leave Montesa, and encouraged Bultó to establish a new company to build sporting motorcycles. Bultó agreed, and in June 1958 he formed Compañía Española de Motores SA (CEMOTO) at his family’s country home on the outskirts of Barcelona.

To form the brand name Bultaco, the first four letters of Bultó’s last name were merged with the last three letters of his nickname, Paco. Their trademark “thumbs up” logo arose from Bultó’s memories of seeing British race mechanics giving their riders the thumbs up sign as they flew past the pits, indicating “all’s well.” Bultaco’s initial goal was to design a 125cc competition motorcycle that could also serve as the basis for a line of production machines. By October 1958, they had completed the first running prototype.

A winning platform

The following spring, in April 1959, the new race bikes proved themselves at their first outing at the Spanish GP at Montjuich Park in Barcelona, where the Bultacos took seven out of the top 10 finishing spots.

In the years that followed, the basic engine architecture of that first road racer — an air-cooled, single-cylinder, piston-port 2-stroke — was carried over into winning road and offroad models in various displacements including road racers (the TSS), street bikes (the Metralla), offroad machines for trials (the Sherpa) and motocross (the Pursang).

A passion for motorcycles

Bultó was not merely an industrialist. From his teenage days he was a motorcycle enthusiast who also competed successfully as a rider. Bultó was amateur champion of Catalonia in 1935 on a Velocette, and in 1948 he was Spanish national champion on a 250cc Montesa.

Many of Bultó’s descendants inherited his love of motorcycles. He had 10 children, and one son, Juan Soler, became Spanish Trials champion and went on to work for Bultaco. Bultó’s nephew, Oriol Puig Bultó, was a leading motocross star who represented Spain in the Trophée des Nations, competed in the annual Six Days Trial, and later served as competition manager for Bultaco. Bultó was proud to see one of his grandsons, Sete Gibernau, compete successfully at the top international level in 250cc and 500cc Grand Prix races.

In a tribute written for Cycle News in 1998 following the death of Francisco Bultó at age 86, journalist and former Spanish road racing champion Dennis Noyes recounted that when the old man was on his deathbed and realized the end was near, he said, “Bring me my moustache wax and my best Bultaco shirt. For a trip like this, you must be at your best.” How can you not respect and admire such a man?

Like Soichiro Honda, who in 1954 declared he would devote his heart, soul, creativity and skills to building a motorcycle capable of winning at the TT races, Francisco Bultó was a visionary leader who recognized the value of success in top-level competition. The two men shared a mutual respect and an uncompromising attitude towards ensuring that every machine they produced would make them proud.

The Bultaco Metralla

From 1962 through 1966, Bultaco made approximately 5,000 200cc Metrallas (also known as the Model 8 or MK62). The choice of the model’s name is puzzling given that “metralla” is Spanish for shrapnel. Clearly, someone in the marketing department had a sense of humor. The engine was all aluminum alloy with cast iron liners and hand-finished transfer ports. Free revving, the engine made about 20 horsepower, which was not too shabby for its size.

The primary case was on the right, engine power transferring through the transmission to the chain final drive on the left, making it easy to change overall gearing by swapping the front sprocket. Shouldered alloy rims, a Monza-style flip-up fuel cap, clip-on handlebars and a big air scoop on the front brake all contributed to the bike’s racy looks.

There was no battery — the flywheel on the left side of the engine incorporated a FEMSA magneto to provide sparks and generator coils to create current for lighting. At low rpm, the lights were weak, and over-revving could cause the lights to burn out — not a great design. Instrumentation was limited to a speedometer, and a kickstarter (on the left side) brought the little beauty to life. It was all thrills and no frills.

The Mk2

In 1967, the factory introduced the Metralla Mk2. The engine grew to 250cc, and output increased to 32 horsepower — good enough for 100mph, making the little Metralla, at least for a brief period, the fastest 2-stroke street bike in the world.

The rear chain was enclosed in a case, the front brake was upgraded to twin-leading shoes and a battery was fitted to keep the lights on when the bike wasn’t running. An oil tank and injection pump were added so that the rider didn’t have to prepare their own premix, and the gearbox grew from four to five speeds. Bultaco made approximately 5,000 second-generation Metrallas before production ceased in 1974.

The Metralla mystique

The Metralla enjoys a well-deserved reputation for excellent road holding and being immensely fun to ride. The frame welds aren’t pretty and there are no exotic tubing materials, yet Bultaco nailed the steering geometry, rigidity and weight distribution — the lightweight Metralla’s ability to grip the road inspires confidence. If Goldilocks rode bikes, she would approve: The balance of handling, power and braking is just right.

A 1965 Bultaco ad stated: “The Metralla is a production racer fitted with street equipment. The 200cc engine has been detuned to 20 horsepower. You still get a reasonable top speed — 85-90mph, stock. But you get fierce acceleration right off idle — 16.7 seconds through the quarter mile — coupled with outstanding reliability. The Metralla will stay with its production-racing brothers in the corners … You can go in so fast that your elbow feels like it’s about to scrub the asphalt.” And this was long before Marc Márquez was even born.

It wasn’t just advertising fluff: In the 1967 250cc Production class race at the Isle of Man TT races, Bill Smith and Tommy Robb finished first and second on Metrallas and set a lap record for 250cc Production machines that stood until 1976. With aftermarket bits like an expansion chamber exhaust, a racing Dell’Orto carb and revised gearing, the little Metralla could run an honest 100mph.

Vincenzo’s Metralla

Vincenzo Murphy bought our featured 1965 Metralla from a friend in Austin, Texas, in 2008. The bike had sat for many years in the back of a poorly lit shed, and it wasn’t until the deal was done and he dragged the bike out into the light that Vincenzo saw how much work it needed.

The old girl was in rough shape. The alloy parts (engine/gearbox cases, hubs/rims, etc.) were heavily oxidized. The chromed parts were peeling and the exhaust system was rusted and dented. The chain guard, taillight and toolboxes were missing. The gas tank had been painted silver with a rattle-can and the front fender was cut in half.

Locating replacement parts was challenging. Most came from Spain and were triple the cost of corresponding parts for a British bike. The toolboxes were found on eBay (their keys came from Spain) and an Australian company custom-built the muffler from Metralla patterns. Not cheap. A fellow Bultaco enthusiast in Houston who used to work at a Spanish bike dealership lent Vincenzo copies of the factory parts and shop manuals. He also provided such new-old-stock parts as the front fender, headlight rim and Spanish-made Amal carb and air filter.

Vincenzo spent many hours wet sanding and polishing the alloy cases, hubs, rims, fork sliders and headlight brackets. Jon Holbrook at Jack’s Paint Place in Converse, Texas, has worked with Vincenzo on various projects for almost 20 years, and his beautiful paint job provided added inspiration to bring the overall level of restoration up a notch. “When the parts came back from Jon, I had no choice but to build a really beautiful bike,” Vincenzo says. “I really value my relationship with him because his work always makes me try hard to get everything right.”

The restoration took six years. What provides the motivation for such a lengthy undertaking? “In order to pull off something like this you really have to be in love with the process,” Vincenzo says. “You need to have a clear picture in your head of the end state. Savor such milestones as getting your paintwork back, your seat refinished, your newly chromed parts and freshly re-laced wheels. It’s these inspirations that will carry you through the rough periods of the restoration.”

When the bike was done, Vincenzo found it lived up to its reputation: “The bike loves to rev and handles like a dream. The power output is impressive for what it is and the time period it represents. It’s probably one of the most fun bikes I’ve ever ridden. It’s the perfect bike for twisty roads. Its looks are perfectly balanced,” Vincenzo says. “The colors aren’t flashy so much as elegant, giving the bike a purposeful, all-business feel. It has an incredible exhaust note. The smell of Castrol when it is running and the way it handles are completely addictive. It really is an amazing motorcycle.”

Vincenzo may be familiar to regular readers of Motorcycle Classics as the owner of the 1924 Beardmore-Precision and the 1949 HRD Comet we featured previously. The man knows motorcycles and his praise for the Metralla carries weight.

Bultaco redux?

In 1977, Bultaco was Spain’s leading motorcycle manufacturer, selling bikes in 68 countries. But by the early 1980s, the Bultaco factory had closed as a result of multiple factors including restrictive U.S. EPA motorcycle emission standards, labor unrest in Spain and an increasingly competitive marketplace.

Today, a consortium owns the Bultaco brand and sells accessories such as helmets, watches and apparel bearing the famed “thumbs up” logo. According to the company’s website, they intend to bring a range of electric motorcycles to market in 2015. We’ll see …

The Bultó family estate where Bultaco was “born” is known in the Catalan language as Mas de Sant Antoni, or San Antonio House. Fifty years after it was first built, this superb Metralla visited another San Antonio half a world away. Like the Bultaco, the 300-year-old Spanish Mission San Francisco de la Espada, in San Antonio, Texas, was built by passionate people. With caring custodians, the Metralla and the building — each understated, elegant and purposeful in its own way — will continue to age with style and grace. MC