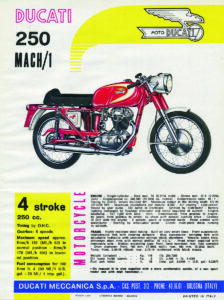

Engine: 248.6cc OHC, four-stroke air-cooled single-cylinder, 74mm x 57.8mm bore and stroke, 10:1 compression ratio, 28hp @ 8,500rpm

Top speed: 105.4mph (170 kmh)

Carburetion: Dell’Orto SS1 29mm

Transmission: 5-speed constant mesh gear primary drive

Electrics: Battery and coil, 6v generator

Frame/wheelbase: Steel single downtube, engine stressed member, 54in (1,350mm) wheelbase

Suspension: 31.5mm telescopic front forks, swinging arm rear suspension with 3-way adjustable Marzocchi dual shocks

Brakes: 7.0850in (180mm) drum front and single 6.2992in (160mm) drum rear

Tires: 2.50 x 18in front, 2.75 x 18in rear

Weight: 255.2lb (116kg) dry

Seat height: 30.4in (760mm)

Fuel capacity: 4.3gal (16ltr)

“He had two large barns,” Don explains, and continues, “he was a racing fan, and something of a hoarder of parts and machines, including pieces of race-crashed Ferraris and all kinds of motorcycles. There was a tremendous amount of interesting stuff in those barns.”

And outside, too. A grainy snapshot Don took in the late 1990s shows a weather-worn 1965 Ducati Mach 1 with a Suzuki for company strapped to a motorcycle trailer. Clearly, both were quickly becoming one with the landscape. Weeds and rust were doing their best to reclaim them, but Don wasn’t about to let that happen, especially to the 250cc Ducati.

Don had known his neighbor since grade school. In fact, he’d once owned and operated Kinkai Suzuki in Appleton and in the early 1970s, Don purchased a succession of Suzuki GT750s from him. This rather informal friendship ensured that in later years, as a neighbor Don could drop in on him and crack a beer and talk about bikes — and about selling them.

While very reluctant to part with any, Don finally convinced him to sell three very disheveled motorcycles — a 1973 Ducati 750 Sport, a 1975 Moto Morini 3 1/2 Sport and this 1965 Ducati Mach 1.

“He thought it was a Diana, but I didn’t think it was,” Don says of the small-bore Ducati. “However, it wasn’t until after I got it that I learned it was the much-rarer Mach 1.”

In 1926 the Ducati brothers, Adriano, Bruno and Marcello, began manufacturing electronic components for radio equipment. The full name of the company was Societá Scientifica Radio Brevetti Ducati, and the corporation was headquartered in Bologna. Other companies might have suffered during the economic conditions of the late 1920s and early 1930s, but the brothers were successful enough that by 1935 they began construction of a brand-new factory. Immediately prior to the war, this Italian firm employed some 7,000 workers.

Ducati, looking for a way to diversify in the postwar economy, began building the 48cc Cucciolo clip-on bicycle motor. The impetus for this engine came from Aldo Farinelli, a Turin-based lawyer who keenly anticipated Italy’s need for cheap and reliable transportation. Together with self-taught engineer Aldo Leoni, the pair built a prototype engine, the first of which was running by 1944. Initially, SIATA (Societá Italiana Auto Trasformazioni Accessori) built the engine, but in 1946 Ducati began production of the unit under license.

More than 200,000 copies of the Cucciolo bicycle engine sold, leading Ducati in 1949 to construct and market its first 60cc motorcycle. In 1954 Ducati hired talented engineer Fabio Taglioni, who, according to author Ian Falloon in his book Standard Catalog of Ducati Motorcycles, 1947-2005, designed the Gran Sport to campaign in the 1955 Motogiro d’Italia.

Of the Gran Sport, which was also known as the Marianna, Falloon writes, “This advanced design formed the basis of all the overhead-camshaft singles through until 1974, and many of its design characteristics feature on the current engines.”

Featuring vertically split sandcast aluminum crankcases that housed both the crank and 4-speed transmission, the top end consisted of an aluminum barrel with a cast iron liner. A two-piece cylinder head made up the combustion chamber, and valve operation was via overhead camshaft driven by straight-cut bevel gears. Falloon states the Gran Sport was hand built in small quantities for racing purposes only, but in 1956 it was available in 100cc and 125cc capacities, followed in 1957 by a larger 175cc version.

The Gran Sport proved to be a very capable race winning motorcycle and Ducati capitalized on its successes in 1956 when Taglioni modified the overhead camshaft single-cylinder engine for mass consumption in the 175 Sport model.

For ease of production, the sandcast cases of the Gran Sport became diecast pieces for the 175 Sport. As well, the two-piece cylinder head became a single casting with enclosed valve springs. Instead of straight cut bevel-drive gears, the teeth became helically cut to help cut down on engine noise. This 174.5cc engine was a stressed member of a single downtube frame topped off with what has become known as the ‘Jelly Mold’ gas tank thanks to its curvaceous and form-follows-function lines.

America’s Ducati importers, the Berliner Motor Corporation, kept pressuring the manufacturer to build a larger-capacity machine and the result was the 200 Elite — or, in the U.S., the 200 Super Sport. From 1959, Ducati had been racing a larger 250cc model known as the Formula 3, and in 1961 the design had been re-worked to become the Monza, a touring machine, and the Diana, a more sporting concept.

In these models, engine revisions included an upgraded crank housed in fresh crankcases and a new cylinder head. Instead of 11 plates, a beefed-up clutch boasted 13 plates to transfer power pulses through the 4-speed transmission to the rear wheel. In 1962, the Monza and Diana were joined by the 250 Scrambler and the Diana Mark 3. Both of these featured, according to Falloon, “… a higher-performance engine, with higher compression, hotter cam and larger carburetor.”

He continues, “Both the 250 Mark 3 and Scrambler expanded Ducati’s change of direction with the overhead camshaft single. There was even more emphasis on off-road and racing performance than the Diana. The Diana Mark 3 came without an air filter or side covers with toolbox, and included new shock absorbers with exposed springs (on most models). There were clip-on handlebars, but normal footpegs and the usual rocking gearshift pedal.”

Getting to the Mach 1 model, we need to focus in here on the Diana Mark 3, a motorcycle that became simply the 250 Mark 3 in 1964 when the 250cc engine gained an extra cog in the transmission to become a 5-speed. In his book Standard Catalog of Ducati Motorcycles, 1947-2005, Falloon describes how the Mach 1 came to be.

“As the 250 Mark 3 was really created to provide American riders with a competitive club racer, it wasn’t widely available in Europe until 1967,” he writes, and continues, “The Mark 3 was also limited in its role as a usable street motorcycle as it didn’t have a battery and the starting was difficult, especially on early models with a fixed ignition advance. In response to European demand for a high performance 5-speed 250 roadster, Ducati created the Mach 1.”

On the market for just two years, from the end of 1964 into 1966, Falloon says it’s the Mach 1 that “…has become one of the most desirable production Ducatis of any era.”

While similar in many respects to the 250 Mark 3, the Mach 1 featured a red frame, and was actually stamped with a frame number. Most other Ducatis imported by Berliner to the U.S. were identified only by the engine number. Once in the U.S., the Berliner Motor Corporation added a sticker with the engine number to the frame.

Very similar in specification to the 250 Mark 3, including rearset footrests and controls, the Mach 1 did differ with its battery and coil ignition and clip-on handlebars. On the Mach 1, either a dual saddle or a sporting solo seat could be specified.

Tucked into the headlight shell was a 150mph speedometer, and according to Falloon, no tachometer was originally specified for the Mach 1. Many restorations, however, have been retrofitted with a tach, and Don added one to his machine. Small, triangular side panels did not cover the battery. Spoked wheels were 18 inches in diameter and had rather narrow chromed steel rims.

There were a couple of changes to the Mach 1 during its short production span, including in 1965 a frame that incorporated a rear brake light switch mount and in 1966 an air scoop on the front brake backing plate. Falloon notes that some Mach 1s were sold with larger side covers — and the right-hand side housed an air filter.

Ducati’s new wide-case single cylinder machines were introduced in 1967, and Falloon says those models featured an upgraded kickstart lever. The Mach 1 has a unique curved kickstarter made to clear the rearset footpeg, which doesn’t allow for a full true “kick.”

As purchased in the late 1990s, Don’s Mach 1 had been modified with a different top fork clamp and was wearing a scrambler-style braced handlebar. At that time, he took the Ducati completely apart and continued researching the model. It was while reading an article about a 250cc Ducati in a motorcycle magazine that he chanced across the name of Henry Hogben.

Hogben ran Ducati Singles Restorations in La Salette, Ontario, Canada. He was a Ducati legend, having built and tuned several single-cylinder machines that won race victories, including an AHRMA championship-winning 250 single in the hands of Jay Richardson. Something of a man of mystery, Hogben had lost his right arm earlier in life, but that didn’t stop him from being a wizard with a wrench. He also continued to ride and had set up a Ducati 450 with clutch and front brake levers on the left handlebar together with a snowmobile-style thumb throttle. Unfortunately, Hogben died in late September 2010.

“It was difficult to establish communication with him,” Don remembers as he worked to connect with Hogben in the early 2000s. “He didn’t suffer fools gladly, and when I told him I had a Mach 1, he said, ‘No, you don’t,’ and went on to tell me he had a registry of all the Mach 1s, ‘And your name’s not on it.’

“But he started asking me questions, like, does it have a red frame? Does it have an M1 in the engine number? When I answered yes to his questions, he said, ‘I guess we’re dealing with a Mach 1’ and that’s when the conversation changed.”

From Hogben, Don managed to get some parts such as the correct clip-on bars together with advice on the restoration. Other new-old stock Ducati parts were sourced from the now defunct DomiRacer. Still more parts came from the late Marshall Elmer of Lakeside Cycle in Menasha, Wisconsin. In fact, it was Marshall who rebuilt the engine.

“While the engine looked bad from the outside when we took it apart, inside it was in really nice shape and we simply honed the standard bore and installed a new piston and rings,” Don explains. “I don’t think the bike had ever really led a hard life — it was just neglected in later years.”

The red paint color was matched to unexposed areas of the frame, while the silver was matched to the color found under the side covers. All paint was applied by the now-retired Bryan Gagnon of B&J Custom Cycles in Shawano, Wisconsin.

One of the hardest pieces to find was the distinctive Silentium muffler. Don can’t recall where he finally sourced the correct unit, but he’s glad he did. He says, “Every time I see a Mach 1 there’s usually something about it that just looks wrong, and it’s often the muffler.”

He did differ from stock specification by adding flanged Borrani alloy wheel rims and stainless-steel spokes. The front tire is 2.50 x 18 inches while the rear is only slightly wider, at 2.75 x 18 inches.

With the Ducati together it took little coaxing to bring the engine to life with its 29mm Dell’Orto SS1 carburetor. However, Don was slightly shocked at the manner in which this was accomplished. He recalls the front wheel being strapped to a trailer, while Marshall Elmer sat on the bike and had his helper drive the truck to “pull start” the Ducati.

“It’s always been an easy bike to start, and I’ve never had any trouble kicking it through with that curved lever,” Don says. “It’s a fun bike to ride because you can carry a lot of speed into a corner and it’s very light.”

There’s no special starting drill, either. Just lightly tickle the Dell’Orto (Don says the original SS1 made hot re-starts difficult, so he installed a new modern Dell’Orto), choke it a bit and kick it through. For the full sound and fury of a Mach 1 ridden at speed, Don recommends watching Nathan Bell’s 1965 Ducati 250 Mach 1: Part 2 YouTube video.

He says, “They sound really good when they’re ridden hard and the engine’s being revved out. His video is very entertaining to watch, and in the cold Wisconsin winter months when I can’t ride mine, I’ll often pull it up and listen to that wonderful sound.” MC