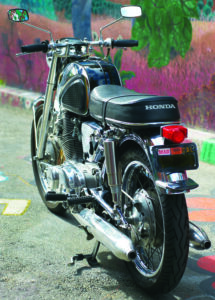

Meet the sporty 1963 Honda CB77 Super Hawk. Styled like a European motorcycle, it helped Honda to meet the American need for speed, looks, and horsepower.

- Engine: 305cc air-cooled 4-stroke SOHC parallel twin, 60mm x 54mm bore and stroke, 10:1 compression ratio, 28hp @ 9,000rpm (factory claim)

- Top speed: 2mph (period test)

- Carburetion: 2 Keihin 26mm carburetors

“Together with the 250cc Hawk, the Super Hawk was the first truly modern motorcycle most Americans encountered: pushbutton starting, reliable electrics, fantastic brakes, 100-plus-mph performance, incredible SOHC sophistication and impressive smoothness.”

— Phil Schilling, Cycle World

After World War II, America was invaded by light, good handling British motorcycles. The English factories made money, the stockholders were pleased and the good times appeared to stretch to the horizon — except for one little problem. Management forgot to upgrade the machine tooling that made the motorcycles. It was not possible to develop the product and, eventually, quality control suffered.

At the same time, Japan, thoroughly ruined in World War II, was struggling to get back on its feet. The Japanese saw salvation through technological upgrades and quality control. With public transportation in disarray, there was a large internal market for small, reliable motorcycles. Soichiro Honda designed such a bike, but, not content to just sell to fellow countryfolk, Honda wanted to export. To do so, he had to overcome the then-bad reputation of Japanese products. In the Forties and Fifties, many people in Europe and America believed “Made in Japan” meant cheaply made, tinny and unreliable. Honda, determined to change that perception, started by arranging bank loans and purchasing Swiss and American machine tooling to the tune of one million 1952 dollars. His shareholders were much more patient than British shareholders, and were content to wait for the investment to make a profit. Although Honda paid his workers about what British workers were paid, Japanese executives did not demand English salaries. Profits were plowed back into the business. By 1959, the same year that Honda started exporting to the U.S., Honda was the world’s biggest motorcycle company.

Moving forward

Honda’s American subsidiaries’ first best seller was the Super Cub, a 50cc step through that spanned the gap between bicycle and motorcycle. Seeking to sell bigger bikes, Honda quickly learned that Americans wanted speed, looks, and horsepower; and were not that interested in fuel economy. Honda engineers were tasked with giving the customers what they wanted. A 250 twin showed up at motorcycle shows in the fall of 1960 as a 1961 model. It came in two versions: the Dream, an economical get-to-work bike, and the sporty Hawk. The Hawk was in many ways a first for Honda: it was styled like a European motorcycle, with a tubular frame and lightweight fenders. Earlier Hondas had pressed steel frames, which were cheaper to produce, but looked ugly and stodgy to American consumers.

In 1962, the cow trail and dirt road capable CL72 Scrambler appeared. Dave Ekins and Bill Robertson rode a pair of highly modified CL72s from Tijuana to La Paz to set a long distance off-road record. This trek sparked the Baja 1000 race. In 1968, Ekins wrote an article for Cycle magazine, explaining what he did to turn a CL72 into a winning race bike. He said he did all of the long list of improvements because the Honda was “reliable,” an important feature when down a dirt road miles from nowhere.

The CB77 Super Hawk appeared in the Spring of 1961, shortly after the 250cc Hawk. The frame was derived from the lightweight racers that Honda was then campaigning. This 305cc twin had an overhead cam, 8-inch double-leading-shoe brakes, and 12-volt alternator electrics, complete with an electric starter at a time when most bikes were making do with kickstarters, single-leading-shoe brakes and 6-volt generators. It also didn’t leak oil — a complete revelation. Magazine testers commented that there was not enough blow-by through the chain oiler to keep the chain greased, but that they preferred greasing chains to cleaning up oily engines. Although fuel economy was not an engineering objective, most Super Hawks will wring about 50 miles out of a gallon.

Honda advertising emphasized innocent fun and respectability, culminating in the “You meet the nicest people on a Honda” campaign. The new imports arrived just as Baby Boomers were reaching their teens and wanting to go places and see things. Soichiro Honda’s combination of a technologically advanced, clean running, reliable product and intelligent advertising made his dream of worldwide sales come true. By December 1962, American Honda was selling more than 40,000 motorcycles annually, including a lot of Super Hawks.

Good reviews for the Honda CB77 Super Hawk

Period motorcycle magazines loved the Super Hawk, and not only because Honda was buying large ads. Cycle World liked the bike so much they road tested it twice. The editors stated in the September 1964 issue: “Although the machine has changed little since that time [the first test in 1962] we are repeating the test. Reasons: we have acquired several new readers over the intervening years; and that the Super Hawk, changed or not, is one of the most advanced and best performing motorcycles available today.” Cycle World revisited the Super Hawk for a third time in 1999, in the context of a Wisconsin ride arranged by a loosely organized group calling themselves the Slimey Cruds. Phil Schilling, the author, explained that below 6,000rpm, a Super Hawk will pull along smoothly, “like a Fifties Plymouth.” The redline was 9,200rpm, and over that the valves would start to float. Between 6,000rpm and 9,200rpm, the Super Hawk roared. It would pound along for miles at engine speeds that would make most contemporaries (notably excepting Ducati) bend valves. “Riders called the CB77 cammy and rev-crazy. They were right.”

The Super Hawk was produced from 1961 to 1967 with incremental changes. Up until 1965, the twins were produced with flat bars. The 1966 bikes had improved forks and higher “Western” handlebars. Earlier machines had speedometers and tachometers with indicators that moved in opposite directions, bottom to top, while later machines had a speedo and tach that both moved clockwise, like those on most Western machines.

Meanwhile, Honda’s engineers were working on a new, improved version of the Super Hawk, which came out in 1968 as the CB350, with updated looks, more power, and a 5-speed transmission. By the time the CB77 was retired, over 72,000 had been sold in the U.S. alone.

The ubiquity of Super Hawks makes finding one easier than finding many other motorcycles of the early 1960s. The later CB350s (and their sister machine, the CL scrambler) have acquired the status of cult bikes. While aftermarket parts suppliers are at the ready to help turn a small 1970’s Honda into the owner’s vision of café racer, rat bike or custom machine, the earlier Super Hawks have not acquired the same status. This makes the Super Hawk perfect for someone like owner Jen Tacy, who wants something a little different. Although Super Hawks are not as powerful as later Honda twins, they have similar bright lights, good brakes, and electric starting. Super Hawks are also reliable if the maintenance is kept up.

The one issue that can arise for a Super Hawk that is intended to be ridden on a regular basis, as Jen rides her bike, is parts availability. Bill Silver in his book Classic Honda Motorcycles cautions that finding Super Hawk parts can be problematic. Honda has stopped making parts for older machines, and aftermarket availability can be hit or miss.

Jen’s Honda Super Hawk

The parts issue hasn’t stopped Jen Tacy from riding her Super Hawk on a regular basis. She says that many parts, especially things that wear out repeatedly, like cables, are actually easy to find, although others, including some engine parts, are harder. With some patience, Jen has been able to keep her bike running and maintain it in stock condition.

Jen’s motorcycle adventures started when a roommate came home on a vintage Puch. “I thought that was cool. I wanted one. Then I thought, ‘Why get a moped — why not get a motorcycle?'” Jen had coveted 1960’s cars as a teenager and owned a 1966 Mustang at one point. She decided to look for a 1960’s motorcycle and ended up with a 90cc Suzuki 2-stroke. But Jen did not know how to work on it and couldn’t find anyone who did. Charlie O’Hanlon, the only mechanic in town who worked on older Japanese bikes, only worked on Hondas. Jen looked for six months until she found a Honda she liked on eBay — this 1963 Super Hawk. It was almost stock, but somehow had acquired a chromed frame. Jen is not sure if the chrome was a factory experiment, a dealer project, or an owner customization.

As purchased, the Super Hawk wasn’t running very well. “The solenoid was out, it needed tires, a full tune-up, new cables and an oil change.” In 2008, Charlie helped her get the bike running smoothly — and then moved to Los Angeles. Jen had grown up with a mother who kept the house repaired and understood how to use basic tools. She decided she needed to learn to fix her bike herself. “I wanted to make it my daily rider.” Even after 60 years, the Super Hawk works well as a commuter and grocery store bike, making chores and the daily round fun. “I just started riding all the time.”

Jen took motorcycle repair classes at San Francisco’s City College and found she enjoyed working on bikes. She met Gregg, her wife, when she saw Gregg riding a 1964 Super Hawk. The two got married a few years ago, and have started a small two-wheeled collection. “I work on all our bikes — Gregg’s four and my five.” In addition to the two Super Hawks, there’s a 1989 GSXR 750, an Interceptor that Jen restored herself, and a new Husqvarna Svartpilen. Jen rides the Super Hawk around town and for shorter trips and the bigger bikes on longer trips. “It’s a day trip bike.” Due to a recent change to working from home, Jen is now only on her bike once a week, instead of every day.

In 2021, Jen took the engine out of the Hawk and sent it to Charlie in Los Angeles. “It was making strange sounds. It turned out the cam was worn. I also wanted to upgrade the pistons.” While the engine was apart, Charlie replaced some worn parts and Jen had the front fender rechromed. Nine months later, the engine came back, all shiny and fresh. Jen installed it in the chassis and is back to riding this bike on a regular basis.

Part of the reason why Jen rides the Super Hawk so much is its ease of maintenance. She replaced the original points with an electronic ignition. “Everything is really easy to access.” The only regular chore is the 500 mile oil change. The bike has a centrifugal oil filter that rarely needs cleaning. Jen checks the carburetors occasionally, but it rarely needs adjustment. “It doesn’t go out of tune as long as I keep riding the bike on a regular basis.” She also occasionally checks the valves. “Adjusting the valves is super easy. I adjust the chain, put air in the tires — that’s about it.”

With the electric starter, starting is almost as easy as on a modern bike, although the Super Hawk does take a while to warm up. “It needs a little choke to start and 3-5 minutes to warm up. If you don’t let it warm, the carbs pop.”

“The Super Hawk is my favorite bike. I like the look. I like the dual exhaust. I like the fact that Gregg has the same bike. It’s easy to work on. It’s a perfect city bike. It looks nice, but no one has ever tried to steal it. I had to park it outside for the first five years I owned it, and I would be worried that it would be stolen, but no one has ever tried.

“It’s still powerful and reliable. It always gets me home. It stops fine. The bike feels very happy and I feel secure and confident riding it.” MC

Originally published in the March/April 2023 issue of Motorcycle Classics.