The Golden Age produced amazing engine designs in Motorcycle Grand Prix from race teams, one of which was the Honda RC116 50cc twin.

- Engine: 49cc DOHC air-cooled vertical twin-cylinder, 35.5mm x 25.14mm bore and stroke, 12:1 compression ratio, 13.7hp @ 21,500rpm

- Top speed: 110mph

That unforgettable era actually dawned June of 1959 when Honda’s fledging GP road racing team, consisting of a small squadron of twin-cylinder 4-stroke 125cc RC142 racers, competed at the Isle of Man TT. While the Honda racers hadn’t reached the same competitive level as their European counterparts, the Honda team was successful enough to earn the Manufacturer’s Team Award, placing bikes in 6th, 7th, 8th and 11th finishing positions. The Golden Age was underway, and soon enough Honda was joined by Japanese motorcycle makers Suzuki, Yamaha, and finally Kawasaki. Together they ruled the roost for nine years alongside MV Agusta and several other established European marques such as MZ, Benelli, Morini, Kreidler and Derbi, among others.

But for the most part, the 1960s belonged to the Japanese teams and Italy’s MV Agusta camp. As race teams tussled for Grand Prix dominance, the world witnessed some amazing and interesting engine designs that popped out of the race shops. Nothing was off limits, either, as engineers created engines in single-cylinder and inline 2-, 3-, 4-, 5- and 6-cylinder layouts that shared the paddocks with bikes boasting square-4 and V-4 configurations. Suzuki even had a 50cc V-3 engine waiting in the wings, ready to race in 1968. But that program was shelved because in February, 1968, Honda, the catbird in the seat and posing as the biggest target in Suzuki’s sights, suspended its motorcycle Grand Prix racing to concentrate on Formula 1 auto racing. Moreover, the FIM (Federation Internationale Motocyclisme) had re-established rules that limited the number of transmission gears (6-speed maximum) and engine cylinders within all classes (50cc/single-cylinder; 125 and 250/2-cylinders, 350 and 500/4-cylinders). Consequently, Suzuki deemed it unnecessary to spend additional funds on what was destined to be a dead end project. The Golden Age lost much of its luster as the manufacturers regrouped to revamp their racing programs for coming years.

So what became of all those exotic, fast and oh-so-titillating Golden Age race bikes? Many were purposely destroyed by their makers, the belief being that whatever technology had been gleaned from their racing pursuits should remain within corporate confines (and coffers). As you can imagine, many rare and historic race bikes were lost during those years, although some managed to survive, later to peacefully reside in museums dedicated to specific brands’ past racing history. Today Honda and Yamaha, in particular, have rather extensive race bike displays housed in museums open to the public. Several other Golden Age GP racers managed to find their own safe havens with private collectors, while other bikes became workhorses for privateer vintage and historic racing teams.

If you can’t beat them, join them

But what if you happened to be a diehard Golden Age enthusiast seeking a Golden Age classic for your very own? It’s probably not going to happen, because very few of those exotic bikes ever existed in the first place, let alone survived. What to do?

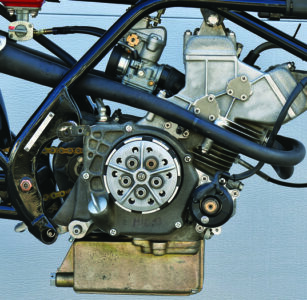

If you’re a skilled draftsman/die-cast engineer/fabricator/welder/mechanic/machinist/tuner/jack-of-all-trades, then you might consider constructing your own tribute or repli-racer. In fact, over time several replicas have actually been constructed by some rather skilled and resourceful individuals, among them a gentleman named Nico Claasen, who built this version of Honda’s RC116, featured here. The RC116 was Honda’s final 50cc racer using a twin-cylinder engine that powered Honda to the 1966 50cc Manufacturer’s World Championship, in the process carrying teammates Luigi Taveri (Switzerland) and Ralph Bryans (Ireland) to second- and third-place respectively in the Rider’s Championship behind Suzuki-mounted Hans-Georg Anscheidt.

As a Grand Prix enthusiast and privateer racer, Claasen has always favored small-bore road racers, building his first 50cc 2-stroke road racer in 1969. Through the years several more Claasen-built racers followed, including a few sporting Honda’s 50cc Dream R customer-based racing engine that favored the marque’s early 50cc factory-backed, single-cylinder racers. By 2006, Claasen determined that one cylinder wasn’t enough — the crafty Dutchman would build his own twin-cylinder RC116 replica.

The RC116 was Honda’s final variant for 50cc racing, its first example being the 1962 RC110/RC111 (40mm x 39mm, 9.5 horsepower @ 14,000rpm, weighing 154 pounds), from which the CR110 production racer was derived with its DOHC conversion kit (40mm x 39mm, 9.5 horsepower @ 14,000rpm, weighing approximately 135 pounds race-ready). The CR110 was certainly fast by privateer standards, but on the world stage of factory-backed teams in Grand Prix racing, it pretty much remained a field filler, nothing else. The CR110’s real glory was found at the amateur, or clubman, level of road racing.

By late 1962, Honda fielded the RC112 (DOHC twin-cylinder, 33mm x 29mm, 10 horsepower @ 17,500rpm, 137.8 pounds), and for 1963 the RC112 begat the R113 (same displacement and horsepower as RC112, weighing a svelte 116.8 pounds), which was later refined by a young engineer named Shoichiro Irimajiri, who in later years was instrumental in perfecting the virtues of Honda’s highly vaunted inline 6-cylinder 250cc and 350cc GP racers. The technology from those projects ultimately paved the way for Mr. Irimajiri to serve as project lead for the production-based 6-cylinder CBX in the late 1970s.

The RC114, in and of itself, was an amazing machine sharing similar bore and stroke as the RC113, but producing 12 horsepower at 19,000rpm, weighing a scant 110.2 pounds. The 2RC114 (no specs available) superseded the RC114 later in the race season, but it was the RC115 for 1965, with its 13 horsepower at 21,000rpm and weighing 110.2 pounds that showed the most promise against Suzuki, Kreidler, Tomos and Derbi 2-strokes, finally winning the Manufacturer’s Championship, with Ralph Bryans first in the rider’s points chase as well. The following year Honda won all five classes (50cc, 125cc, 250cc, 350cc and 500cc) in the Manufacturer’s Championships. That also happened to be when the RC116 (35.5mm x 25.14mm, 49.77cc, 13.7 horsepower @ 21,500rpm, 110.2 pounds) debuted. By year’s end and with eyes cast towards a full season of Formula 1 auto racing, Honda throttled down its motorcycle GP racing, electing to field entries only for 250cc, 350cc and 500cc classes in 1967. As noted, the company officially withdrew entirely from motorcycle GP road racing in early 1968.

Where to start?

Claasen began his personal RC116 project in 2006, the plan being to build two replicas, one for him, the other for a racing friend. Unfortunately his partner had a serious racing accident shortly after they got underway and had to drop out, leaving Claasen with two bikes on his build docket.

Obviously Claasen had his work cut out for him, recalling, “There is, of course, logic in building an engine and I had collected a lot of pictures (of the RC116).” Claasen said that the photos offered him a starting point in which he could measure one particular item (such as wheel diameter) and use that dimension to gauge and determine proportional scale for other parts on the bike as well. “The only thing I couldn’t figure out from pictures (of the bikes) was the shape of the camshafts and the return of the oil lines, and other internal parts.” He based the crankshaft’s dimensions on the engine’s bore and stroke, plus he was able to gauge the engine cases’ external measurements. He also opted to make copies of the CR110’s gear cluster that would easily fit into the cases’ small confines, rather than replicate the RC116’s original, and more complex, 9-speed box.

As for castings, he enlisted the aid of specialist Eling Bouwstra for help. Claasen describes Bouwstra as a master of his trade; “I learned a lot from him. The cylinder head was the most complex in terms of pattern-making as well as casting.”

Shortly after undertaking the project, and by chance, Claasen sold his successful yacht-building business. Overnight he gained more time to devote to the RC116 project, and as the engine began to come together he managed to make headway on the frame, made of seamless mild-steel drawn tubing. “No molybdenum,” he makes clear.

Meanwhile, work proceeded on the engine where some ingenious engineering took place. For instance, the 4-valve combustion chambers have Ampco 45 inserts, made of special bronze alloy that Claasen was able to shrink-fit into each combustion chamber. He claims the alloy inserts are “very good” for their intended use. Two slide-body 16mm Dell’Orto carburetors were “slightly modified” to resemble the original Keihins that Honda originally used.

Claasen was most concerned about the crankshaft because the original Honda 50cc racers had feather-light cranks; minimal reciprocating mass meant that the little engines could rev quickly and fully through their 22,000-plus rpm power curves. The downside, of course, was little or no flywheel weight, which meant little or no flywheel effect under racing conditions. That combination also made those tiny race bikes a challenge to ride. If a rider doesn’t feed the carburetors proper throttle at all times, doing so can easily stall the engine. Ralph Bryans, who joined the team in 1964, made that point very clear after his first experience riding the tiddler-class Hondas he was assigned to ride, stating, “No one told me how to ride it. The only thing I was told was that minimum revs was 19,500, and off I went.” Bryans, who established his reputation riding British singles, promptly discovered that blipping the throttle while downshifting — a common practice that the surly single-cylinder Norton 500s with their heavy flywheels demanded — caused a major problem. Simply, as the rider (in this case, Bryans) instinctively sought to match the RC116’s engine speed with transmission speed, the laws of physics told the engine to do otherwise, and to revert to zero rpm. That created a major issue with Bryans’ RC116. “The valves tangled,” recalled Bryans, “and that was that.” Translation: he broke the engine — three times before he figured out the problem.

As for the replica’s crankshaft, Claasen says, “There have been no crankshaft problems. The shaft is exactly like the original.”

He continues: “The biggest problem was valve springs because I wanted to do it with one spring (per valve), but it (the engine) only went well when I also applied an inner spring as Honda did.” Well, it is a “replica”!

Speaking of Honda, engineers familiar with the original RC116 said that Claasen’s plan couldn’t be done. But as the determined Dutchman made progress, those same engineers began tuning in to the project, even giving it their support. However, for the most part what you see here was due to Claasen’s dedication and acquired skills, not any inside help of consequence.

For instance, the original RC116 racer used a magneto for ignition, but with today’s advancements in electronics, Claasen created his own ignition system, concealing a small battery under the front portion of the slim gas tank (like the original, fashioned out of aluminum) to retain authenticity. The coils remain in view as with the original, so to make them look period correct he placed them in aluminum pipe, “which I then wrapped with original tape (as used in the ’60s) and then in colored lacquer” to resemble what was used in 1966.

Eventually a complete engine emerged, allowing Claasen to show it at a race in Belgium at the famous Spa Francorchamps racetrack. In attendance was former Honda racer Ralph Bryans, who was rather surprised and amazed that one man could create such a realistic clone.

By 2012 the project was finished, and a short time later another ex-Honda rider, Luigi Taveri, was on hand to view it, sharing some history about when he raced those small-bore Hondas during the Golden Age. Indeed, Taveri won quite a few races and finished second in the 50cc Rider’s Championships for 1965 and 1966.

Dutch treat

Claasen never raced his RC116, but he continues with his 50cc road racing hobby, currently dabbling with a 2-stroke twin. His new goal is to get the little oil-burning engine to produce 25 horsepower. As for the two RC116s that he completed, he sold one to Holland-based aftermarket parts company CMS. Most recently this one found a home with another small-bike road race fan, former French 50cc national champion Philippe de Lespinay.

Now a resident of California, de Lespinay knew Claasen well, as he had previously purchased the Dutchman’s Derbi “RAN” machine. De Lespinay inquired if the Honda RC116 clone was for sale, and after several months, Claasen accepted his offer. The bike recently joined the expatriated Frenchman’s collection of other 50cc and 125cc road racers, among them his own Garbage Can Special that he built, raced and won the AFM 125cc championship with at club races back in the 1970s. Shortly after the RC116 arrived in California, de Lespinay gave it a quick cleaning before displaying it at the Trailblazers’ Tom White Memorial Bike Show where it won the Best of Show blue ribbon. It followed that with another award at the Classic Motorcyle Festival, held at Willow Springs Raceway. Proof that the Golden Age still has some luster to it.

There may never be a time in road racing again that’s as exciting, even romantic, as the Golden Age. But through the efforts of diehard enthusiasts like Nico Claasen, Philippe de Lespinay and others, it’s possible for us to remain connected to a time of our racing heritage that was, in many ways, more precious than gold itself in terms of the technology and innovation that it offered. MC